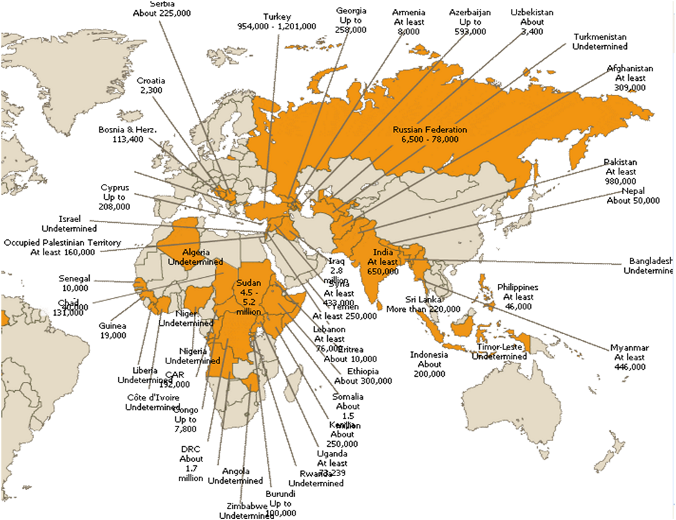

“IDMC monitored internal displacement in 21 African countries. All but two of these fell in the category of countries of low human development; the only exceptions were the Republic of the Congo (medium human development) and Algeria (high human development), while Eritrea and Somalia were not ranked at all due to a lack of data.

In these 21 countries, 11.1 million people were internally displaced by conflict and violence at the end of 2010, down from 11.6 million a year earlier. The fall marked a continuation of a sustained downward trend since 2004, when there were 13.2 million IDPs on the continent. Africa was the only region in which the number of IDPs decreased in 2010. Despite the overall downwards trend, the region also saw large forced population movements in the course of the year.

40 per cent of the world’s IDPs were in Africa. Sudan ac- counted for more than 40 per cent of the African total, with around five million people displaced in various regions. Along with Colombia, it was one of the two countries most affected by internal displacement in the world. Darfur alone, with between 1.9 and 2.7 million IDPs, had more IDPs than the two next biggest situations in Africa, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (1.7 million IDPs) and Somalia (1.5 million). IDPs in Sudan, DRC and Somalia together represented more than 70 per cent of all IDPs in Africa.

The gradual decline in IDP numbers masked large new movements in individual countries. The first ten months of 2010 saw 220,000 people newly displaced in Southern Sudan, and 270,000 in Darfur. In DRC, the total went down from 1.9 million IDPs in 2009 to 1.7 million in 2010, but several hundred thousand people were newly displaced in 2010, while between mid-2009 and the end of 2010 an estimated million IDPs return- ed to their villages. Similarly, while the total number of IDPs in Somalia was steady in 2010 at 1.5 million, in the course of 2010 at least 300,000 people had to flee from their homes.

Other countries in Africa which saw new displacement in 2010 were the Central African Republic (CAR), Côte d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal and Zimbabwe.

Causes of displacement

In most countries, displacement was caused primarily by conflict between the government and armed opposition groups, or by inter-ethnic violence. Important exceptions in 2010 included CAR, where armed bandits have been the main cause of displacement since 2008, and Zimbabwe, where almost all displacement was due to unlawful evictions carried out by, or condoned by, the state.

Elections were a major factor behind some of the new displacement in Africa in 2010. In Côte d’Ivoire, disputed presidential elections in November led to violence and displacement. About 3,000 people had been displaced by the end of the year and their number was growing: the UN made contingency plans for up to 450,000 IDPs in 2011. In Nigeria, clashes between supporters of rival candidates broke out in 2010, months ahead of presidential and legislative elections scheduled for 2011, leading to localized short-term displacement. In Sudan, nationwide elections took place in April 2010 after many delays, followed by a referendum on independence in Southern Sudan in January 2011.

Protection concerns of IDPs

IDPs in many African countries faced insecurity and violence, including attacks by armed groups against civilians. Violent attacks by the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) continued to cause significant displacement in a number of countries. The LRA originated in Uganda, but since the signing of the Cessation of Hostilities Agreement between the LRA and the Ugandan government in 2006, it has been more active in neighboring countries, notably DRC, Sudan and CAR.

Sexual violence, including rape, continued to be a particular problem, notably in eastern DRC. The forced recruitment of children, including internally displaced children, was reported in countries including Chad, DRC and Somalia.

IDPs in many conflict situations in Africa had more difficulty than non-displaced people around them in accessing basic necessities including food and clean water. In Somalia, food security deteriorated in IDP camps across the country in the course of the year as a direct result of violence. Even in more stable situations where food distribution programmes were not hampered by insecurity, many IDPs were unable to provide for themselves as they could not establish livelihoods.

Lack of access to justice, whether in relation to cases of sexual violence as for example in DRC, or in relation to land disputes in the aftermath of conflict, continued to be a major issue for IDPs across the continent.

There were reports of certain groups of IDPs facing additional hardships on the basis of their ethnicity. In parts of central Africa, the Batwa were particularly discriminated against: in both Burundi and DRC they were living in more difficult conditions than other IDPs. Pastoralist groups such as the Peuhl in CAR lost their means of supporting themselves and also faced discrimination when displaced into sedentary communities.

Limited monitoring or information on IDPs

In some countries most IDPs had gathered in informal or organized camps. The large camps in Darfur hosted many tens of thousands of IDPs. The informal camp near Afgooye in Somalia, hosting close to 500,000 people who had fled nearby Mogadishu, was thought to be the biggest settlement of IDPs in the world. However, in DRC, Nigeria and elsewhere, the majority of IDPs had dispersed among hosts who had given them shelter, and in countries across the region from Kenya to Liberia, Nigeria and Algeria, large numbers of people had been dis- placed to cities where they remained unidentified.

In almost all countries monitored by IDMC, limited capacity was dedicated to gathering and analyzing data on internally displaced populations, and so there was a persistent scarcity of information on their numbers, location and demographic make-up, the conditions in which they lived and the assistance they required. In some countries, such as Ethiopia, government restrictions on humanitarian and human rights organizations prevented even basic monitoring of displacement.

Even in countries such as Uganda where good data was generally available, there was little information about groups of IDPs with specific needs, such as older IDPs and those with long-term health problems. In these countries there was also little information on people displaced into urban areas. Elsewhere, it was difficult to put together the analysis of different agencies: in DRC, a study found that agencies used different procedures for monitoring IDPs and different methods for analyzing their data, making it difficult to compare information.

However, some countries took positive steps to gather better data: in Nigeria, where monitoring generally focused on people who sought shelter in temporary camps, to the exclusion of those who stayed with relatives or friends, the government appealed to the UN to support a wider profiling exercise.

Information on the conditions in which long-term IDPs in post-conflict situations lived remained extremely limited in 2010. Even in countries where fairly detailed statistics were available about return movements, it was rare to have information about the extent to which IDPs were achieving durable solutions. In some countries, such as Algeria, governments insisted that there were no longer any IDPs, when in fact there had been no exercise to verify whether IDPs had managed to settle permanently or what assistance they might still need.

The lack of monitoring was particularly acute in relation to IDPs who remained in their place of displacement: it was often not clear whether there were particular obstacles to their return, or they had chosen to settle permanently there. People displaced into cities had often gradually adapted to urban lifestyles, and did not intend to return to their rural homes even when security permitted. Their settlement choices formed part of the general rural-to-urban migration trend in Africa. In Darfur, forced displacement had contributed to rapid urbanization: many IDP camps had become semi-permanent urban centres, despite the government’s insistence on eventual return. Displacement also contributed to the urbanization of Southern Sudan, where there were no IDP camps and many IDPs settled in the towns instead.

National responses

In a number of countries the government took positive steps to respond to internal displacement. The government of Burundi adopted a reintegration strategy for people affected by the conflict and set up a technical IDP working group. The government of CAR was in the process of developing a national legal and institutional framework to address internal displacement. In Kenya the government finalized a draft national IDP policy, although by the end of the year it had yet to be adopted.

A number of other governments struggled to mobilize the will or resources needed to develop and implement IDP response strategies. In CAR, Chad, DRC and Nigeria, the ministries and government bodies put in charge of the response did not have sufficient capacity to have a real impact on the lives of IDPs. In Côte d’Ivoire, elements of a national legal framework to protect the rights of IDPs were still awaiting signature, years after being drafted. The Ministry for Reconstruction and Reinsertion, which had been supporting IDP return movements in 2009, was abolished in 2010. Overall responsibility for IDPs was moved from the Ministry of Solidarity and War Victims to a new secretariat, which further put into doubt the government’s commitment to signing the draft legal framework protecting IDP rights.

Some governments were criticized during the year for failing to address internal displacement. Seven independent UN human rights experts reported that the government of DRC had neglected its responsibilities to protect and assist IDPs, while UNHCR recommended that the government of Niger do more to protect the rights of IDPs.

In some countries insecurity prevented a response to internal displacement. For example, in DRC, 120 security incidents involving humanitarian staff were recorded in the first six months of 2010, twice as many as a year before.

In 2010, CAR, Chad, Sierra Leone and Uganda became the first four countries to ratify the African Union Convention for the Protection and Assistance of IDPs in Africa (the Kampala Convention), which had been adopted by the AU in October 2009. By the end of the year a total of 31 countries had signed the Convention. It will come into force once it has been ratified by 15 of the 53 AU member states.

International responses

Two UN peacekeeping forces saw significant changes in 2010. In DRC, the UN Mission in the DRC (MONUC) was replaced with UN Organization Stabilization Mission in the DRC (MO- NUSCO), while in Chad and CAR the UN Mission in the CAR and Chad (MINURCAT) forces were withdrawn altogether at the request of the government of Chad. Both UN and AU peacekeeping forces came in for criticism: the forces in DRC were accused of failing to protect IDPs and other civilians, while the AU force in Somalia reportedly caused new displacement, with the force being accused of deliberately shelling civilian areas in retaliation for insurgent attacks.”